At 854m in height, Arenig Fawr lays no claim to be amongst the mightiest of peaks in Snowdonia. The late W. A. Poucher ranked the rocky summit of this remote mountain as 24th in an ordinal list of the Welsh Peaks. But a mountain is more than a mere measurement of its ascent above ordnance datum, as obsessive peak-baggers and list tickers may fail to acknowledge. It is a massif of geological history, an eco system of flora and fauna, a facilitator of meteorological phenomenon, a catalyst of story, myth and legend, a home of spirits from an earlier age.

I first fell under the spell of this less well known area of the Welsh mountains as a student at Aberystwyth University. As Michaelmas term progressed and the nights began to draw in around the somewhat claustrophobic collegiate town, we looked with increasing anticipation to our weekend forays into the Welsh countryside to find space and light. And so we stumbled across the mountains to the south of Llyn Celyn, since when something has called me back time and time again.

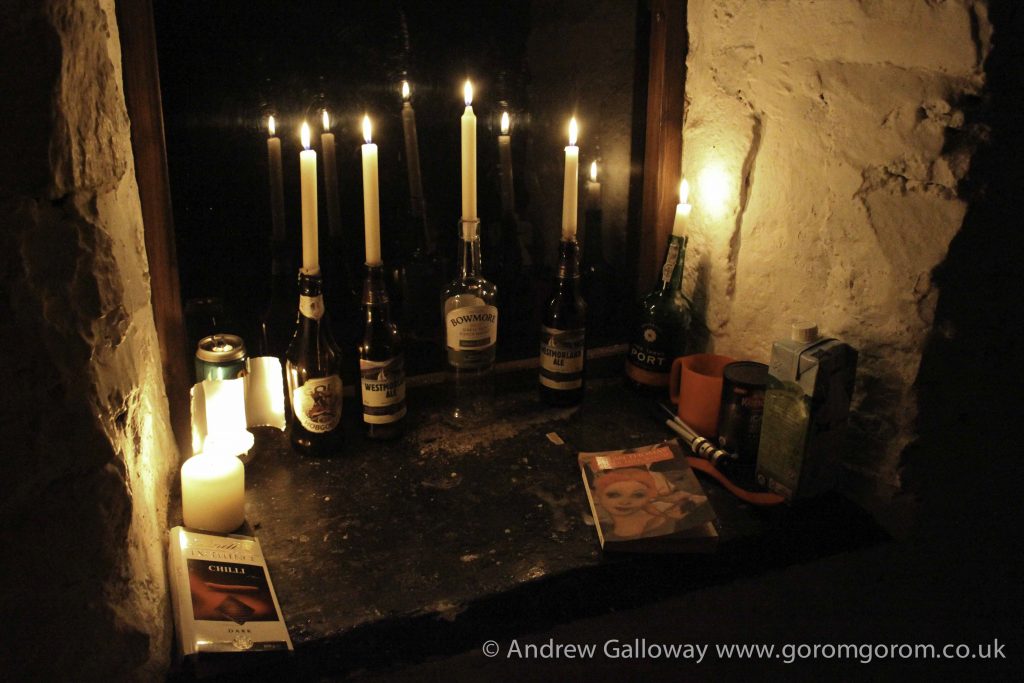

On the autumnal equinox I set off to spend the night at the MBA hut situated rather apprehensively just below the slightly Heath Robinson looking dam at Llyn Arenig Fawr. As the hut is situated less than two miles south of the A4212 Y Bala-Trawsfynydd road I decided to extend the journey by starting at the Llyn Celyn dam, picking my way through the farms and fields around Mynydd Nodol and crossing a rather boggy Nant Aberderfel, where the Ordnance Survey indicated path seems to vanish into purple moor grass, bog myrtle and waist-high heather. After four rather gruelling miles I arrived at the bothy, which was, thankfully, empty. The hut is only just large enough for one person, or perhaps two if they know each other well, and probably dates from 1830 when Llyn Arenig Fawr was first adapted as a reservoir to provide the town of Y Bala with drinking water. The lake gains some shelter from storms as it lies in the lee of the crags of Simdde Ddu, but as an autumnal wind began to get up across the silvery waters, as the light began to fail and the rain began to pitter-pat on the steel chimney cap, I determined the best course of action was to light a fire in the somewhat smoky grate and settle down for the night.

Llyn Arenig Fawr Bothy

In geological terms Arenig Fawr was born 490 million years ago in a sea of fire and foam in a part of geological time known as the Ordovician. The collision of continental plates gave rise to an arc of fierce volcanic activity. The volcanoes erupted into a shallow sea with explosive force, spuing out pyroclastic flows of white-hot ash and lava, which roared with breathtaking speed into the surrounding waters, making them boil and hiss. These “nuées ardentes” or burning clouds, rapidly cooled in air, in water to form solid rock: ignimbrites, tuffs, breccias, from which the lofty crags of Arenig Fawr were chiselled.

During the last ice age some 14,000 years ago, sheets of ice would have submerged these valleys, with only the mountaintops protruding above, a veritable flood concealing the fertile valleys from hunter gatherers and forcing them south to warmer climes. As the valleys and human imagination began to emerge from beneath the ice, stories were woven by the Celtic people about a race of giants who lived among them. Idris was one such giant, living upon his seat “Cadair Idris” and who would initiate contests between other giants, Yscydion, Offrwm and Ysbryn who also lived amongst these hills and mountains. There is an account in the Welsh Triads of the bursting of Llyn Llion that resulted in the deaths of all living people, with the exception of Dwyfan and Dwyfach, who escaped in a boat without sails, and went on to repopulate the British Isles with their offspring. Arenig Fawr seems a likely place for the grounding of this mythological boat, the Welsh for Ark being Aren or Arene. Similarly, it is believed locally that the ruins of an ancient and legendary city lie beneath the waters of Llyn Tegid, or Bala Lake as it is know in English, once lost in a great flood. The lake, formed by glacial melt waters following the last ice age, is one of the last habitats of the Gwyniad fish, a small salmonid creature. Three rather forlorn looking specimens of this remnant of a post-glacial ecosystem sit pickled in formaldehyde in the White Lion Hotel on the main street of Y Bala. Another local legend tells of a farmer who once found a fairy calf among the rushes of Llyn Arenig Fawr, and reared it as one of his own cattle. For many years it produced many fine offspring, making him a wealthy man, until one day a small man playing a pipe appeared by the lake and by his eerie music, led the animal back into the waters to rejoin the fairy herd. Born from water and returned to water.

I awoke to a cold, wet, grey morning and struggled to raise myself from the warmth of my sleeping bag. After a breakfast of kippers cooked on the old iron pan I found hanging on the bothy wall, I carefully balanced across the rickety old iron ladder spanning the water out-flow of the dam, and began to ascend the limb of Y Castell to the south-west of the lake. As I climbed higher and the expanse of open country to the south gradually began to reveal itself, I could see three sheets of water dominating the landscape: Llyn Celyn to the north, Llyn Arenig Fawr in the corrie below, and across the moorland to the south, Llyn Tegid, cradled in the valley beneath the lofty crags of Aran Fawddwy.

The spirit of Arenig Fawr can be deceptively passive, imbued with an air of amiability, beneath which lies a dark and angry character. On clear spring days, with the song of skylarks lifting high into the azure sky, the climb to the summit is a little more than a strenuous walk. But in winter, when the mountain is draped in snow and ice, reminiscent of that long ago age, when black clouds tear across the summit ridge propelled by winds strong enough to lift walkers from their feet and dash them onto the jagged rocks below, then one might imagine giants battling in these hills.

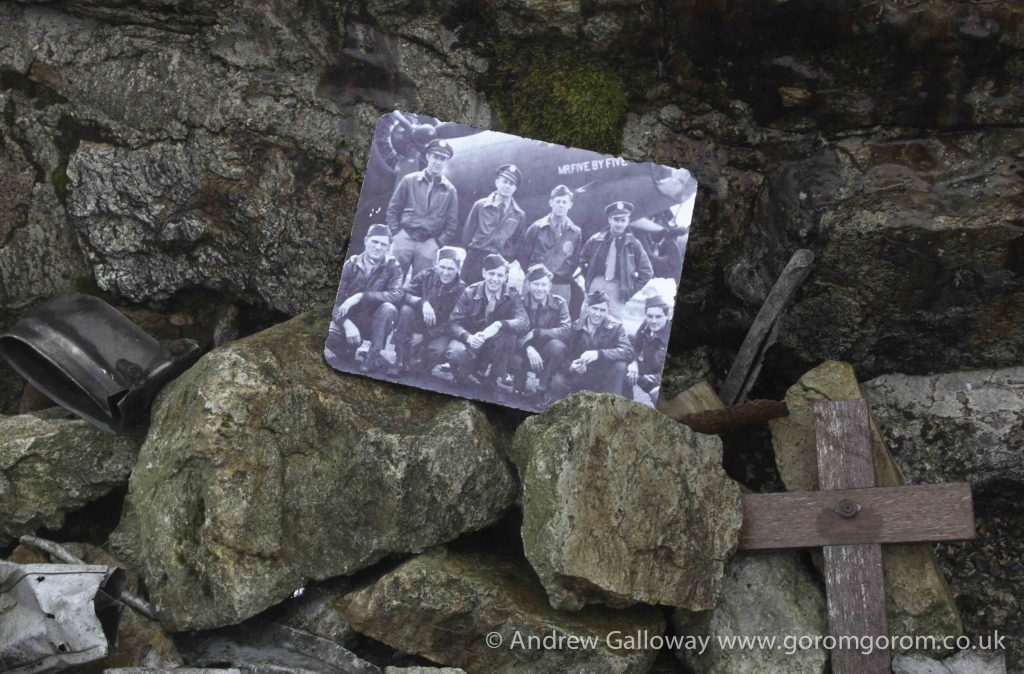

On a moonless August night in 1943 the deep thrum of aircraft engines could be heard above the wind, echoing along the Dyfrdwy Valley. The aircraft was a United States Air Force B17 Flying Fortress, “Mr Five-by-Five”, on night training manoeuvres, many miles off course. It is thought that the crew never saw Arenig Fawr in the darkness. Had the aircraft been just fifty metres higher they would have cleared the summit ridge, secured their location and returned to base for cocoa and a good night’s sleep. The summit cairn now bears a slate memorial to the eight American crewmembers, each one originating from a different state of the Union, who were killed that night. The area is even now scattered with fragments of metal, mostly fused, one would suspect at very high temperature, into the volcanic breccias that form the rocky outcrop, such that it is impossible to tell where aluminium ends and the natural rock begins. The bodies of the crewmen were never found.

Memorial to the crew of the United States Air Force B17 Flying Fortress

To the south of the summit, Moel yr Eglwys, Church Hill, lies an area of rare simplicity and beauty where a scatter of crystal-clear pools, encircled by rich, red bog grasses, lie amongst undulating crags and rocky tors. Westward, across the boggy col of Ceunant Coch, I climbed to the summit of Moel Llyfnant and was rewarded with a view across Coed-y-Brenin, the King’s Forest, to the Rhinogydd, dark and silent like sleeping giants, beneath a blanket of cold-grey cloud.

To the north of Moel Llyfnant, on the descent towards Amnodd-bwll and Amnodd-wen, there are remains of shielings, or hafod in Welsh, buildings associated with the summer grazing of livestock, probably dating from the 18thCentury. Many are of considerable size and extent, belying the once active agricultural history of this barren landscape, populated now only by walkers, lone forestry workers and the occasional sheep.

In twenty-four hours I saw not one other person until I reached the sleepy hamlet of Arenig, from where I crossed Afon Tryweryn to reach again the A4212, where the cars and lorries race at foolish speed. Circling the lake I was reminded of the latest tale in these chronicles of fire and flood. In 1965, the construction of the reservoir of Llyn Celyn, built to provide water to the city of Liverpool via the river Dee, resulted in the flooding of Capel Celyn, a small village, which was a centre of welsh cultural activity. Local bitter feelings were exacerbated by the insensitivity of the authorities involved and the passing of the legislation for the reservoir in Parliament despite the opposition of thirty-five of the thirty-six incumbent Welsh members. The incident is remembered as a moot point for advocates of the Welsh Language, most notably by a piece of graffito on the wall of a ruined stone cottage by the A487 at Llanrhystud, outside Aberystwyth bearing the inscription “Cofiwch Dryweryn” Remember Tryweryn.

Cofiwch Dryweryn

Arenig Fawr is an old, old mountain and has seen much in its lifetime, has many stories to tell of giants and fairies, fire, ice and flood. And although now it ranks as only a lesser Welsh peak, in a wild and desolate location, it has the spirit of a fiery volcano still.