One of my most treasured books, which I return to for reference more than any other book I possess, is The Poet’s Manual and Rhyming Dictionary, first published by the American academic and poet Frances Stillman in 1966. The dogeared copy on my bookshelves was purchased in 1991 upon it’s eighth re-print, since when it has influenced and informed my understanding and appreciation of poetry. An invaluable pre-internet resource for any aspiring poet, in addition to a complex and comprehensive rhyming dictionary her book contains seven chapters outlining the traditional structures, meters, rhymes and forms of poetry as appreciated towards the termination of the twentieth century, illustrated with excerpts from many well known poets and a modest scattering of her own verse.

City College New York

Although copies of her books can still be found in second hand bookshops and even on certain online book forums, sadly, Stillman herself seems to have slipped into obscurity. A brief obituary from the New York Times dated 5 February 1975 reads as follows:

“Dr. Frances Jennings Stillman, assistant professor of English at City College and a writer and translator, died Monday at New York Hospital of complications resulting from kidney failure. She was 65 years old. Dr. Stillman, who also had taught at Brooklyn and Hunter, Colleges, was the author of “The Poet’s Manual and Rhyming Dictionary.” She translated “Flemish Tapestries,” written by Roger D’Hulst, and “Oriental Love Poems,” among other works. For many years, she was an officer in the New York Chapter of the American Association of University Women. Dr. Stillman earned B.A. and M.A. degrees at the University of Michigan and a Ph.D. degree at the City University of New York.”

It was Dr Stillman who, through her book, introduced me to the lyrical form known as the Sapphic, named after the enigmatic Greek poet who lived on the island of Lesbos during the sixth Century BC.

The historical biography of the poet known as Sappho is fragmentary and speculative. She was believed to have been born on the island of Lesbos around 620 BC. During antiquity she was regarded as one of the finest lyrical poets of the time. Plato revered her as the tenth muse (in Greek mythology there were traditionally believed to be nine muses devoted to poetry, history, music, dance and astronomy, amongst other things).

Many of Sappho’s poems have been lost, and much of those that survive do so in fragmentary form, but her influence upon modern poetry, particularly the Romantic movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, cannot be understated. Her poems have been translated by Sir Philip Sidney, Percy Shelley, George Gordon, Lord Byron, Alfred Tennyson and many others, including the nineteenth-century Greek poet Aléxandros Soútsos. The spontaneity, simplicity, and honesty of her verse strongly influenced the Romantic idea of the poet as a creature of feeling, one whose solitary song is overheard, as opposed to the classical didactic model of the poet as a cultural spokesperson.

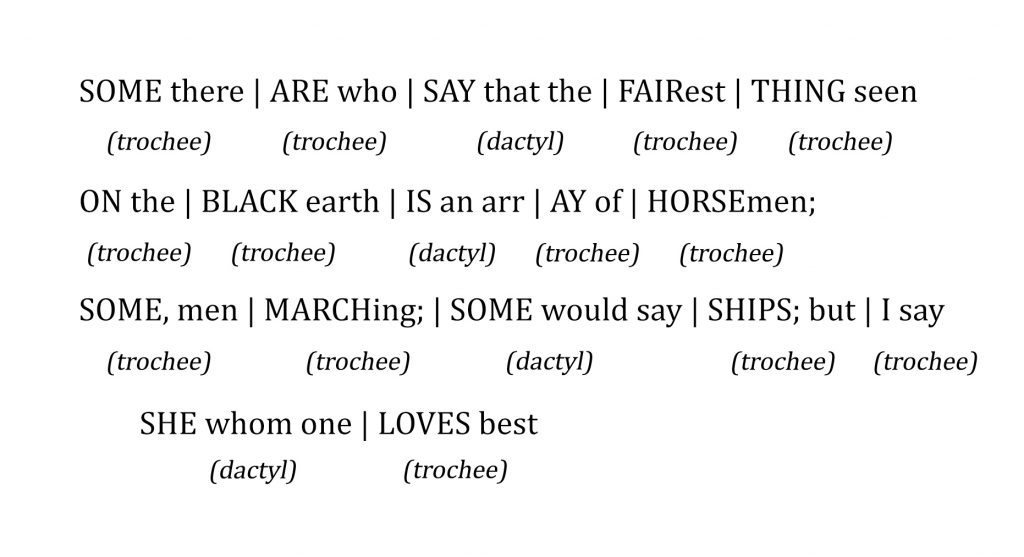

As Dr Stillman teaches, the main building blocks of the sapphic are trochees and dactyls. The trochee is a metrical foot with one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable, while the dactyl contains a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables. The first three lines of the sapphic contain two trochees, a dactyl, and then two more trochees. The shorter fourth, and final, line of the stanza is called an “Adonic” and is composed of one dactyl followed by a trochee.

The following deconstruction uses a verse from a modern English translation of Sappho’s Anactoria poem.

The extant fragment of this poem explores Sappho’s longing for her lost love Anaktória, and her admiration of the female form.

Some there are who say that the fairest thing seen

on the black earth is an array of horsemen;

some, men marching; some would say ships; but I say

she whom one loves best

is the loveliest. Light were the work to make this

plain to all, since she, who surpassed in beauty

all mortality, Helen, once forsaking

her lordly husband,

fled away to Troy—land across the water.

Not the thought of child nor beloved parents

was remembered, after the Queen of Cyprus

won her at first sight.

Since young brides have hearts that can be persuaded

easily, light things, palpitant to passion

as am I, remembering Anaktória

who has gone from me

and whose lovely walk and the shining pallor

of her face I would rather see before my

eyes than Lydia’s chariots in all their glory

armoured for battle

The erotic homosexual content of many of her poems has won Sappho the accolade of being the first (first recorded at least) Lesbian, the very term being derived form her Aegean island home of Lesbos. Undoubtedly, it was the freely erotic components of her work that fascinated certain protagonists of the Romantic movement, who in their own somewhat chauvinist way were striving to break free of the cultural conventionality of eighteenth and nineteenth century society.

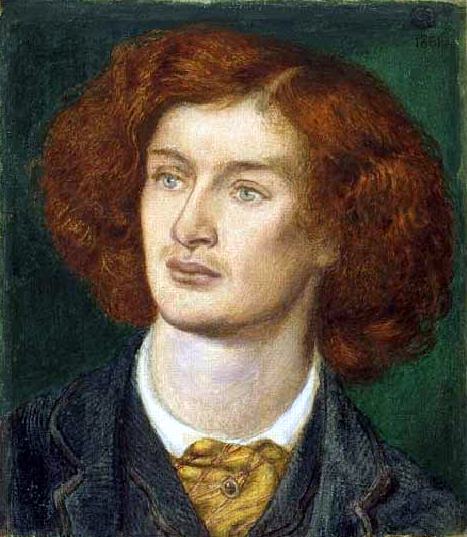

Perhaps the most accomplished Romantic exponent of the Sapphic form was Algernon Charles Swinburne. Very much a product of the English Victorian establishment, born to a wealthy family in the North East of England, educated at Eton and at Balliol College, Oxford, Swinburne none-the-less became a preeminent symbol of rebellion against the conservative values of his time. Greatly influenced by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other member of the Pre-Raphaeltie Brotherhood, his poems were often explicitly sexual, perhaps designed specifically to shock the very establishment from which he came. Swinburne gained notoriety in 1865 with the publication of Poems and Ballads, a collection of poems which many critics of the time regarded as indecent.

The fragment below is taken from his poem Sapphics, written in the Sapphic meter as described above and undoubtedly in homage to the poet Sappho.

All the night sleep came not upon my eyelids,

Shed not dew, nor shook nor unclosed a feather,

Yet with lips shut close and with eyes of iron

Stood and beheld me.

Then to me so lying awake a vision

Came without sleep over the seas and touched me,

Softly touched mine eyelids and lips; and I too,

Full of the vision,

Saw the white implacable Aphrodite,

Saw the hair unbound and the feet unsandalled

Shine as fire of sunset on western waters;

Saw the reluctant

Feet, the straining plumes of the doves that drew her,

Looking always, looking with necks reverted,

Back to Lesbos, back to the hills whereunder

Shone Mitylene;

Many years ago, inspired by Dr Stillman’s tutelage, I put pen to paper and came up with the poem below, which I called Castaway. It is based on the myth of Calypso, as told in Homer’s Odyssey, who detained the Greek hero Odysseus on the island of Ogygia during his long voyage home from the Trojan wars.

Wreckage adrift on blue Aegean waters

Clinging the rope cut fingers burn and blister

Slowly cracking the salty sun bleached timbers

bake in the sunlight

Came I to these islands by currents rolling

Red kelp and oyster shell over and over

Till bound in their shackles washed ashore on her

shingle she found me

Almond Oil and Meadow sweet, fresh mint from the

Mountains, yellow Broom and Oak flower petals

Smoothed by her spidery fingers worked warm through

my still dormant flesh

Lips part to tongue touching teeth with each whisper

Soft scent of apples her dark anaesthesia

Heady the night the breath of her warm body

falls sleep over me

Daylight gold in her hair veils sweet soft hollows

Wine blushed lips taste the damp dew of the morning

Naked children of an absent god giggle

at their honesty

Long shore pull drags the hissing shingle seaward

Roar of the deep wave beckons the shifting tide

Impudent voice of reason voice of motion

still calling, calling

Frances Jennings Stillman obituary from the New York Times: accessed 6 August 2019

https://www.nytimes.com/1975/02/05/archives/dr-frances-stillman-dies-english-professor-at-city-65.html