Staffordshire Moorlands

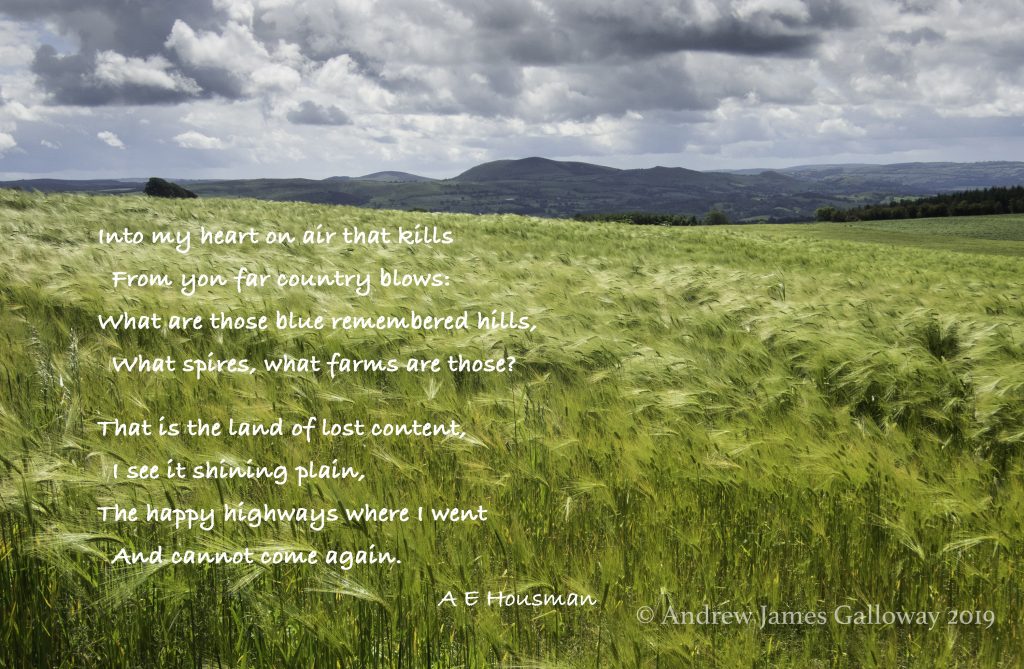

The Staffordshire Moorlands are nothing if not a surprise. In the formative years of my exploration of the Peak District, I was astonished to discover that a sizeable portion of the gritstone uplands of Britain’s most popular national park, including the village of Flash, at 463 metres (1,519ft) above sea level the highest in Britain, lie within the administrative county of Staffordshire, more famous perhaps for pottery, Stoke City football team and the dolesome Alton Towers amusement park. More recently, as I find my time increasingly consumed by worldly concerns, it is among the nearby hills and dales of the Peak District that I find solace.

So with Hallowe’en fast approaching, the turning of the year echoed in the turning of the leaves to amber hues, I had hitched a lift from an old friend to the market town of Leek, from where I intended to make the long journey home to Manchester on foot.

Approaching the hamlet of Upper Hulme along Whitty Lane, the sky to the west began to cloud over grey and the fresh smell of cold air heralded light rain, which soon turned into a heavy downpour. Before long I found myself beneath the slim finger-like battlements of Hen Cloud – Cloud being a Staffordshire dialect word for hill – and sought to take shelter in a small wooden shed, which had been erected by the side of the road. These impressive towers of Carboniferous stone extending almost vertically into the leaden sky constitute the most southerly outcrop of the gnarled and contorted sandstone escarpments that are collectively known as the Roaches, their name being taken simply from the French word for rock.

By the tiny dwelling I was accosted by a man bedecked in dark green waterproofs, clasping a large and slightly threatening pair of binoculars. “Can I help you?” he ventured, and for a moment I wondered if, given recent seismic political movements in the country, the Countryside Rights of Way Act 2000 had overnight been repealed and I was trespassing on ‘his’ land. I subsequently noticed that I was standing beside a large and colourful banner proclaiming the work of the Staffordshire Wildlife Trust, which I had not previously noticed having been cocooned within the hood of my waterproof jacket in a vain attempt to keep out the driving rain.

The gentleman in question was not an irate gamekeeper but rather an enthusiastic volunteer named David who wanted to show me a pair of nesting Peregrine Falcons who had taken up residence some weeks earlier in the lofty fingers of Hen Cloud. “Do you see that central finger of rock, up there?” he pointed through the now stair-rod thick rain to the top of the aforementioned hill, “well, if you drop down on the crag about fifteen feet you can just see where the nest is.” I couldn’t see a thing and David offering the use of his steamed up binoculars made little difference, but for a good twenty minutes the pair of us stood there in the criminally torrential rain, two relatively sane, intelligent men, becoming increasingly saturated, trying to spot a pair of nesting birds of prey who probably had far better sense and were bunkered down within a protective crevice high up on the south face of Hen Cloud waiting for the storm to pass. In many ways I wanted to prolong this very British folly but I made my excuses to David, consulting both my watch and map, thankfully both contained within a waterproof casing, as to the next leg of my journey, and left him to his stewardship of the mighty Peregrines of Hen Cloud in the rain.

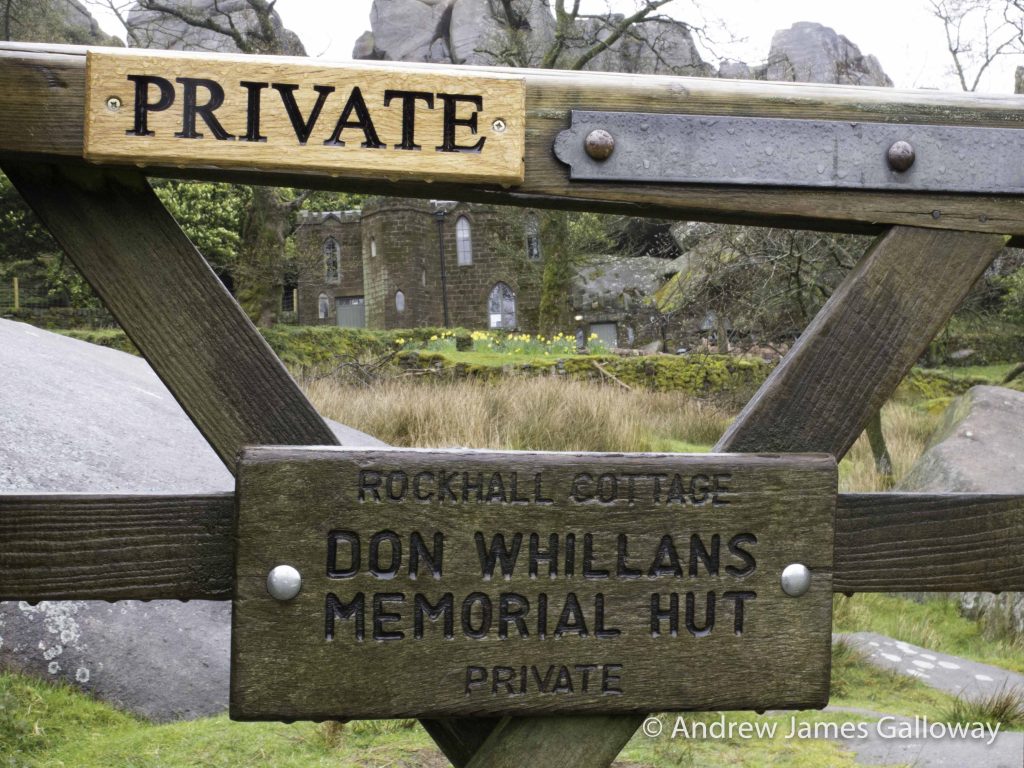

Don Whillans Hut

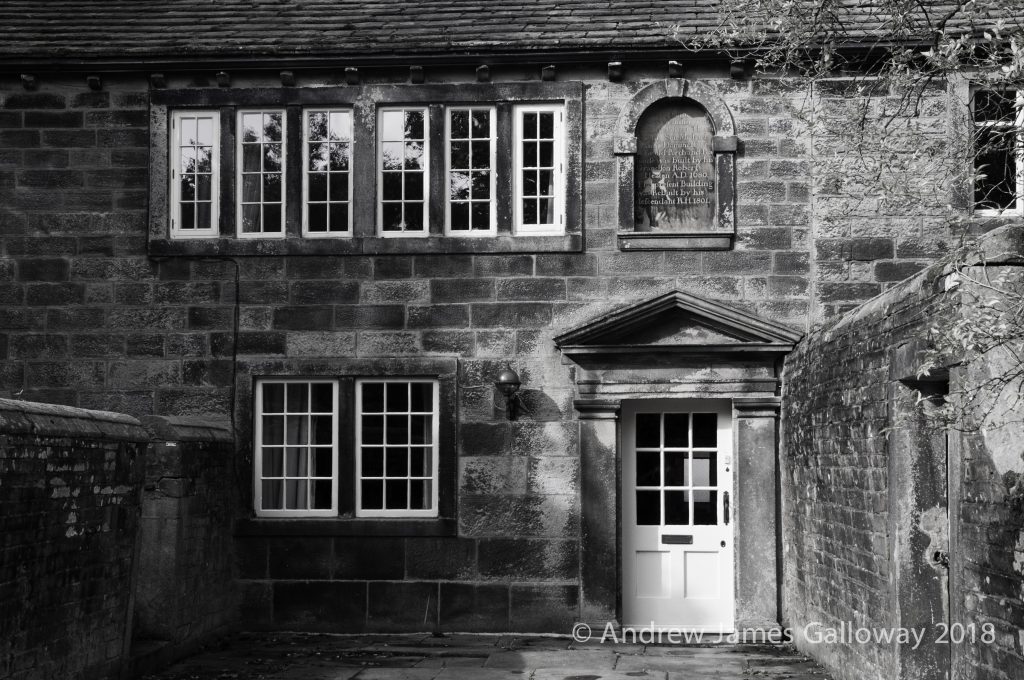

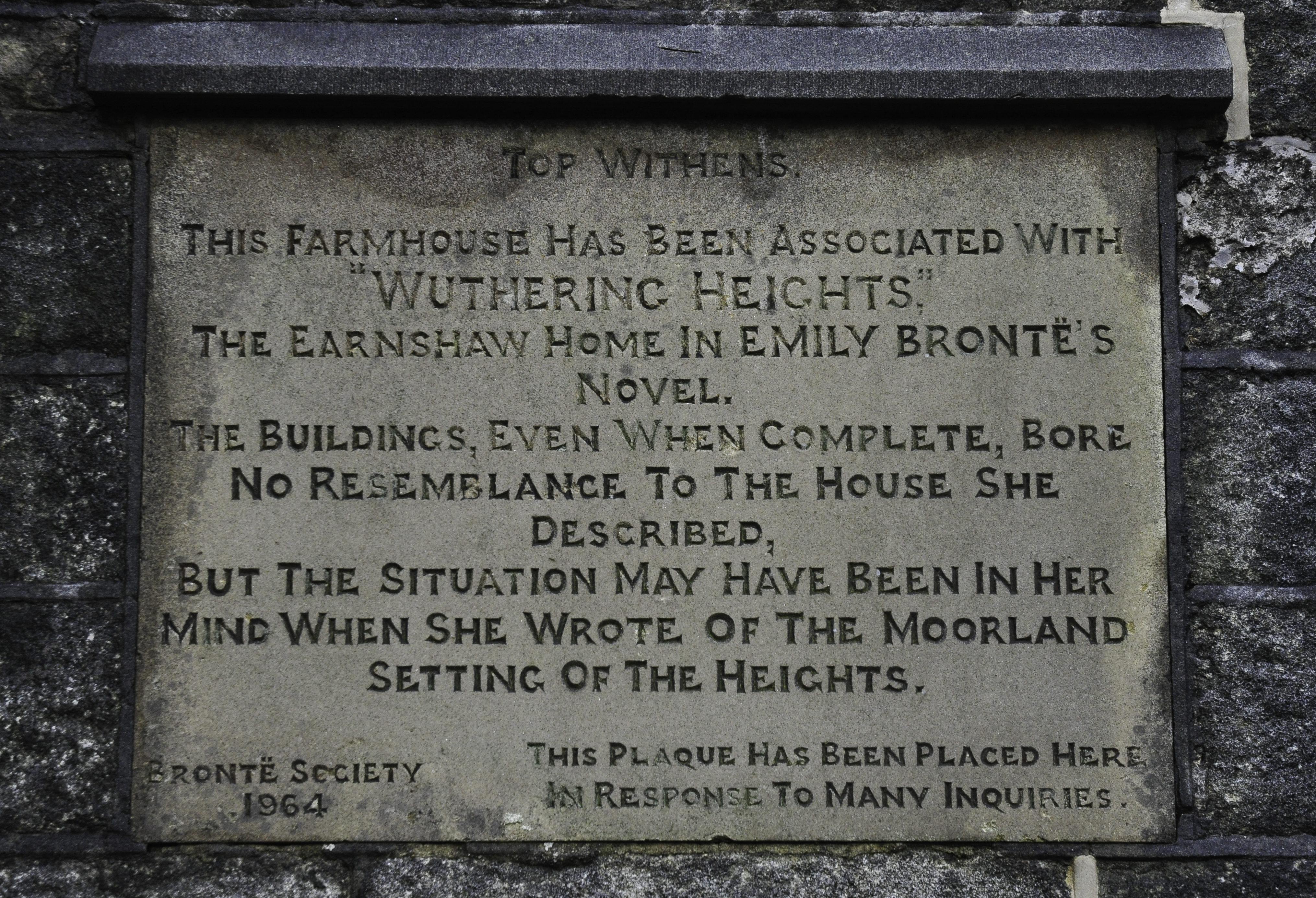

Nestled beneath the lower escarpment of the Roaches, half enclosed by the earthen-red rocks themselves, stands Rock Hall, formerly a summer house of the Roaches Estate, now owned by the British Mountaineering Council and given the epithet of the Don Whillans Memorial Hut. Don Whillans, a dour, stocky Salfordian with as much a taste for scrapping as for making breakthrough climbs on northern grit during the 1950’s with his buddy Joe Brown, is a bit of a hero of mine. Don, who grew up on the hard knocks streets of post-war Salford in Greater Manchester and quite literally punched above his weight when it came to breaking into the elitist world of British climbing, put up some of the landmark climbs on Peak District grit, most notably, at the Roaches. In his beautifully written biography of Whillans “The Villain” Jim Perrin describes how on 21 April 1951 Don had travelled to Leek by bus and having walked up to the climbing crags on the lower tier of the Roaches had watched as Joe Brown’s second had been unable – or unwilling – to follow the line of Joe’s ascent of Valkyrie buttress. Don had quickly volunteered to take up the slack, sprightly following Joe up the route that they later named as Matinee (grade HVS 5b) because of the crowd that had gathered to watch the spectacle. This was the first recorded climb of these luminaries who would go on to revolutionise traditional climbing. Just three years later Joe Brown and Don Whillans would have moved on from the gritstone crags of the Roaches, via the volcanic crags of Clogwyn Du’r Arddu in Snowdonia, to the lofty needles of the Alps, making the first ascent of the Petit Dru West Face, Chamonix in 1954.

The Don Whillans Memorial Hut, owned by the British Mountaineering Council

Whillans went on to be a leading figure in the British mountaineering community of the 1960’s and 1970’s completing the first ascent of the Central Pillar of Freney on Mont Blanc with Chris Bonington and Ian Clough in 1961, the first ascent of the Central Torres del Paine, Patagonia again with Chris Bonington in 1963 and most famously the first ascent of the south face of Annapurna with Dougal Haston in 1970. Don Whillans sadly died in his sleep on 04 August 1985 – he was just 52 years old.

As I ascended the climbers’ steps at the rear of Valkyrie Crag to the second tier of the Roaches, the weather turned from inclement to tempestuous. The occluded Atlantic front which earlier that day had swept across the Western Approaches of the British Isles now slammed into the elevated ridge of the Roaches with all the malignant force of the wailing Banshee supposed to inhabit the moorland tarn known as Doxey Pool, beside which I now stood. Surmising that the Banshee’s curse had certainly come upon me by virtue of hail stones like shot pellets which now dug themselves into the saturated sandy ground around me with sufficient velocity to create tiny craters, I struggled manfully away from the accursed pool with as much speed as I could muster, soon arriving at the white washed ordnance survey triangulation pillar that marks the highest point along the ridge. I continued bravely northwards, losing some altitude through the swirling mists and biting hail, until I caught a glimpse of a sizeable object sheltered in the lee of a dry stone wall.

Being chilled thoroughly to the bone by precipitation as cold as a widow’s elbow, I considered the possibility that first stage hypothermia had set in and as a consequence I was hallucinating, when the object in question assumed the tangible form of an ice-cream van, its colourful logos enthusiastically advertising ice-cold drinks, various flavours of ice cream and cheerfully exhorting me to ‘have an ice day!’ Salvador Dali himself could not have conjured up such a surreal juxtaposition. I considered ordering a ‘ninety-nine’ but my fingers were too cold to open the pocket in my rucksack where I had stashed away some lose change. Thinking better of it I pushed on and as I followed what sometime earlier that day had been a path but now was most definitely a stream, towards Gradbach Wood, the hailstones ceased their torrent of abuse, and in their place came a relatively welcome fine British drizzle.

Lud’s Church

Amongst the mixed deciduous woodland of Back Forest on the north facing slopes of the Dane Valley, where larch, pine and hazel give way to a plantation of slender silver birch trees, is hidden a narrow chasm, sunk some twenty metres into the fractured millstone grit. My understanding of this curious feature is that it is post-glacial in origin, most probably having formed following the retreat of the ice caps at the end of the most recent glacial maximum, some twelve thousand years before present. It is essentially an expansion crack, as might appear as the result of settlement in the plasterwork of new buildings. In much the same way, as the weight of ice was removed from the land and isostatic uplift resulted in geomorphological instability, the rock has fractured, moving several metres into the Dane Valley, itself a product of glacial run-off waters, the line of fracture exploiting weaknesses in the Carboniferous rocks that may have existed for millions of years. This geomorphological phenomenon is known locally as Lud’s Church, the etymology of which is anything but certain.

Myth’s and legends gather about Lud’s Church just as the emerald mosses, ferns, grasses and liverworts cling to the near vertical walls of the chasm. Being in shade for much of the year, the direct rays of the sun only penetrating the depths of the ravine during the season around midsummer when the midday sun is directly overhead, Lud’s Church provides the perfect habitat for woodland species that are able to exploit the dank, moist ledges, crevices, corners and fissures in the rock face on the cavern walls. Rock ledges are garlanded with Oak and Holly Ferns. Wood sorrel grows in abundance among Elegant Silk Moss (pseudotaxiphyllum elegens) and Crescent-cup Liverwort (lunularia cruciata) and where the dominant species allow, waxy green lichens such as Sticta Canariensis take a hold, punctuated by the occasional cluster of Cladonia coccifera or devil’s matchsticks.

Followers of the 14thCentury non-conformist preacher John Wycliffe, known as Lollards, were thought to have met at Lud’s Church for religious worship in order to avoid persecution. It is believed that following one such secret meeting a notable Lollard, Walter de Ludank was arrested here, the chasm thereafter taking his name.

A popular misconception holds that the term Lud’s Church is associated with the Luddite movement of the early 19thCentury. This is no the case. Luddites were textile workers, mainly in the north of England, who protested against the mechanisation of the textile industry by the deliberate vandalism of new weaving technologies such as stocking frames and power looms. Any similarity in name is purely coincidental. Despite these associations, and further legends that other notables employed the chasm as a refuge from authority, including Robin Hood, Friar Tuck and Bonnie Prince Charlie, is more likely that the name ‘Lud’ has a much older etymology and may be Celtic or pre-Christian in origin.

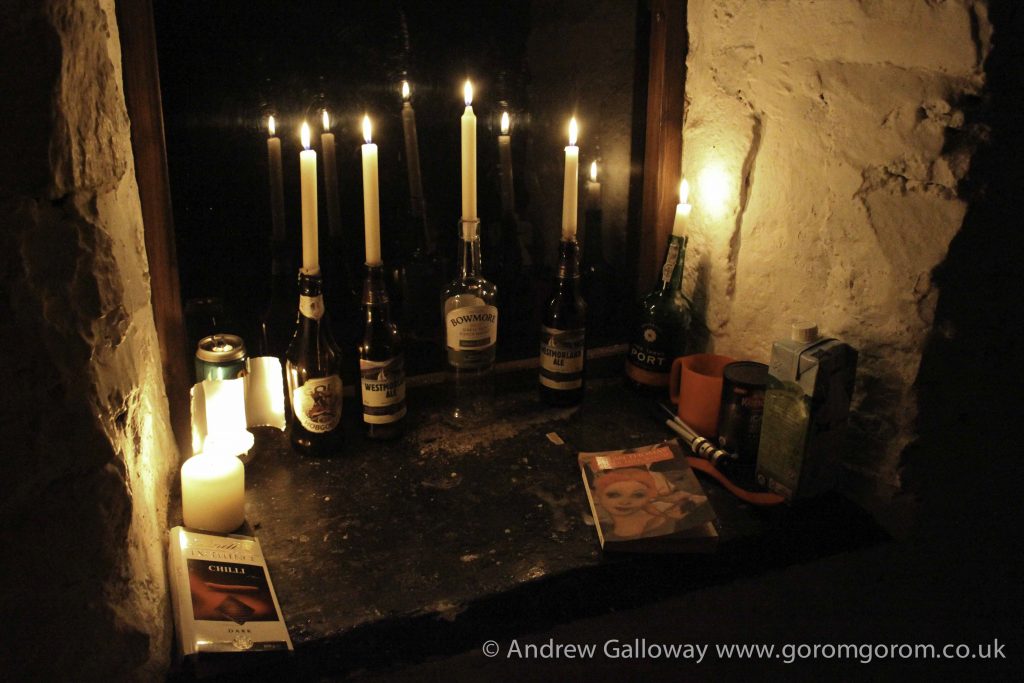

Sir John Rhys, the 19thCentury pioneer of Celtic philology, identified several characters from the collection of medieval Welsh folk tales known as the Mabinogion as potential Celtic deities. One such character is Nudd, whom Rhys believed to be cognate with the Roman-British deity Nodens, or Núadu in the Irish literature. It was Sir John’s belief that three specific characters from the Mabinogion could be linked to the deity of Nudd, these being Lludd Llaw Eraint (Silver Hand) father of Creiddylad who appears in the Arthurian tale of How Culhwch won Olwen, Lleu Llaw Gyffes (Skilful Hand) whom appears in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion and Lludd ap Beli, ruler of the Island of Britain and brother of Llefelys, the primary characters in the brief tale of Lludd & Llefelys. Rhys, partly influenced by the French historian Henri d’Arbois de Jubainville, went even further to suggest the existence of a pan-Celtic deity combining all of these characters known as Lugus (Hutton, 2013). It was this association that linked the name of Lud’s Church in Staffordshire with worship of the pagan god Nodens. In contemporary times Lud’s Church is still an important location for those practicing the Wiccan or neo-Pagan path of spirituality to which the presence of a votive coin log in the main chamber of the chasm attests.

Gawain

Taking medieval linguistics as prima facie evidence, scholars generally agree that the Staffordshire Moorlands are the dialectal epicentre of a piece of late 14thCentury poetry written in Middle English, known to the British Library as manuscript Cotton Nero A. xbut more widely known as the tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. This surviving manuscript, which would easily fit in the palm of your hand, was held in a private collection in Yorkshire during the 16thand 17thCenturies. It was first edited and printed in the original Middle English in 1839 and most famously translated into modern English by JRR Tolkien and EV Gordon in 1925.

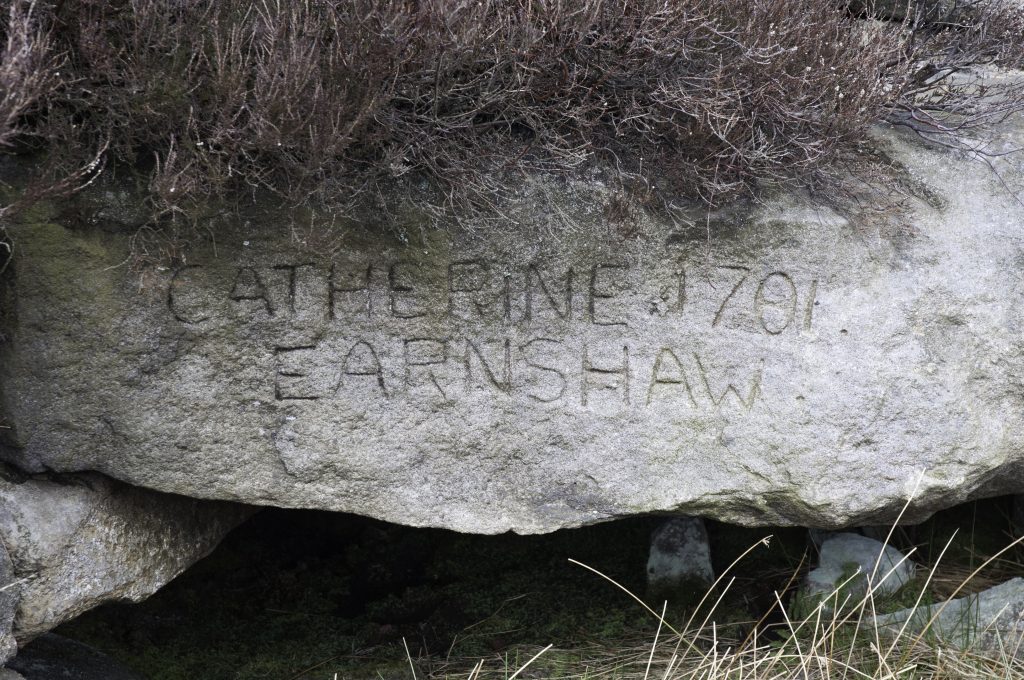

Thought to have been transcribed around 1390, the alliterative poem is without doubt one of the finest examples of medieval poetry in the English tongue and tells the story of a young, perhaps somewhat naïve knight of King Arthur’s court named Gawain whom is challenged to a rather gruesome duel by a most curious and unearthly creature.

The Story begins at Christmas time as the King’s courtiers are enjoying the commencement of a fortnight of feasting, when the festivities are disrupted by the arrival of a ghastly creature, half man half ogre who seemingly unchallenged rides into the court astride a green horse, himself dressed in garments of emerald green, his hair and skin the very same colour. The uninvited guest lays down a challenge before Arthur and his knights, that he will permit any such knight brave enough to take up the challenge to strike him at the neck with an axe, on the understanding that the very same knight will seek out the green ogre at the turning of the year to receive from him the very same blow. Thinking he cannot possibly lose this strange engagement, the young Gawain steps forward to accept the challenge and with a single swing of his axe cleanly smites the Green Knight’s neck, the severed head coming to rest at the feet of King Arthur himself. The assembled guests look on in horror as the beheaded Green Knight steadies himself, then grasping the bright green locks of hair, picks up his own head from the reed strewn floor and turning to Gawain, repeats the terms of the pledge, counselling Gawain to keep his word or be forever known as a coward. With all mouths agape the Green Knight mounts his green horse and, head in hand, gallops from the hall. Over the course of a year, Gwain is forced to overcome many obstacles and temptations before he ultimately finds his way to the Green Chapel, with which Lud’s Church is colloquially associated, to keep his ominous appointment with the ghoulish Green Knight, the outcome of which I will refrain from revealing.

Naturally, doubt exists as to the validity of the transposition of a fictional story onto an actual geographic location, but standing within the richly abundant cascade of verdant plant life, everywhere alive with the whispered drip, drip of water, it is easy to see how the human imagination could transform the deep, narrow rock chasm into the cathedral nave of some long forgotten nature cult, or the great hall of some malign ogre or pagan god.

Emerging from the rank foliation of Lud’s hidden Church, blinking in the now brilliant sunlight of early afternoon, I saw ahead of me the outcrop known colloquially as Castle Rock, where I found a suitable prospect from which to view the valley below. Vaporous pennons of mist rose incrementally upward from the body of the forest, the saturated trees exhaling into the clearing sky, patches of blue breaking apart the sulphurous clouds. Having rested, I descended through the forest to Gradbach Mill, no longer a place of textile production but a beautifully situated youth hostel, alongside which, by means of a narrow stone bridge I crossed the ebullient waters of the River Dane, into Cheshire.

Macclesfield Forest

At Heild End Farm I crossed the A54 Buxton Road and wound my way passed a fine, though slightly dilapidated two storey barn, its slate roof still more or less intact, an ideal place to shelter from a storm or even spend a night, should one find oneself benighted on the moor, and dropped into the vale of Wildboarclough. By the time I reached the Crag Inn the weather had turned around again and the fresh smell of rain and the vanguard of descending, distended drops forced me to stop and adjust my clothing. The east slope of Shuttlingsloe is the steepest of the sharks-fin hill, known locally with much conviviality as the Cheshire Matterhorn, and I certainly felt the pull of gravity on my calf muscles as I laboured my way to the hills crazy-pathed summit. Sticking my head above the outcrop of Chatsworth Gritstone on the south east edge of the hills summit plateau, I was met with a blast of cold, damp air a across the Cheshire Plain translucent sheets of rain swept inwards, propelled by cadaverously oppressive clouds. I elected not to linger and instead descended rapidly to the north and the relative shelter of the Sitka Spruce plantations of Macclesfield Forest, finding shelter beneath the interlaced branches of pine needles as swathes of sleet blew in form the west.

To the north I took refuge from the inclement weather inside one of the jewels of the western Peak District. As the dates above the gabled entrance indicate, the Forest Chapel, or Saint Stephen’s Church as it was consecrated, was almost entirely re-built in 1834 following a fire, but stands on the site of a former chapel of ease constructed in 1673, the stone bearing this inscription having been preserved from the original building. To step inside the Forest Chapel is to step backwards in time to the austere non-conformist existence of the generations who have eked out a harsh living from the bleak Pennine moorlands since the Royal Forest of Macclesfield became common land in the 15thCentury.

I sat for some time as rainwater from the stone-clad roof collected in the lead guttering and splish-splashed onto the paving outside, until ultimately the light in the chapel brightened and brief shafts of sunlight, at acute angles from the south transept windows, blessed the silent nave, and the rain stopped, like the silence that follows the prayers of four hundred years. Outside, a Highway’s sign proclaimed Charity Lane unsuitable for motor vehicles, the very sandstone bedrock having been exposed by years of runoff water from the surrounding hills. As I contoured the higher ridges, the forest below me exhaled again into the now blinding evening light, plumes of vapour rising effortlessly through the suddenly undisturbed forest. I had been walking for over ten hours and as I climbed the steep hard-set path towards Tegg’s Nose, the sacroiliac joints of my pelvis began to complain vociferously. Not wishing to chance a sustained injury, I staggered down the Old Buxton Road to Macclesfield Station from where with prospects of real ale and painkillers, I telephoned a friend and procured a bed for the night.

This article first appeared in The Great Outdoors magazine.